Understanding Satellite Deorbiting

So, space is getting a bit crowded, right? We’ve got all these satellites zipping around, doing their thing, but what happens when they’re done? They don’t just vanish. This is where satellite deorbiting comes in, and it’s becoming a pretty big deal.

The Growing Challenge of Space Debris

Think of space like a busy highway, but instead of cars, it’s satellites. As more and more get launched, especially those huge constellations of small satellites, the risk of collisions goes up. When satellites crash or break apart, they create more debris – little bits of junk floating around. This junk can then hit other satellites, causing more debris, and so on. It’s a cycle that could eventually make certain orbits unusable, a scenario scientists call the Kessler Syndrome. This isn’t just a theoretical problem; it’s a real threat to current and future space operations, from scientific research to communication services.

Defining Satellite Deorbiting

Basically, satellite deorbiting is the process of intentionally removing a satellite from its orbit at the end of its mission. The goal is usually to guide it back into Earth’s atmosphere where it will burn up, or to move it to a less crowded ‘graveyard’ orbit. This isn’t always a simple task. Some satellites are designed with this in mind from the start, while others might need a little help.

The Kessler Syndrome Risk

We touched on this already, but it’s worth repeating. The Kessler Syndrome is a theoretical situation where the density of objects in low Earth orbit becomes so high that collisions between objects generate a cascade of debris, each collision creating more debris to increase the probability of further collisions. Imagine a chain reaction of space junk. If this happens, it could effectively shut down access to space for generations. It’s a stark reminder of why we need to manage our orbital environment responsibly.

Passive Satellite Deorbiting Technologies

When we talk about getting rid of old satellites, not everything needs a rocket or a robotic arm. Sometimes, the simplest solutions are the best, and that’s where passive deorbiting tech comes in. These are systems built into the satellite itself that, when their mission is done, just sort of… help the satellite fall back to Earth a bit faster. They don’t need any extra commands or power to work; they just do their thing based on physics.

Think of it like this: a satellite is zipping around in orbit. The Earth’s atmosphere, even way up there, is still a thing, and it creates a tiny bit of drag. Passive systems are designed to make that drag a lot more effective. The main idea is to increase the satellite’s surface area or create a force that pushes it downwards, making it hit that atmospheric drag harder and faster.

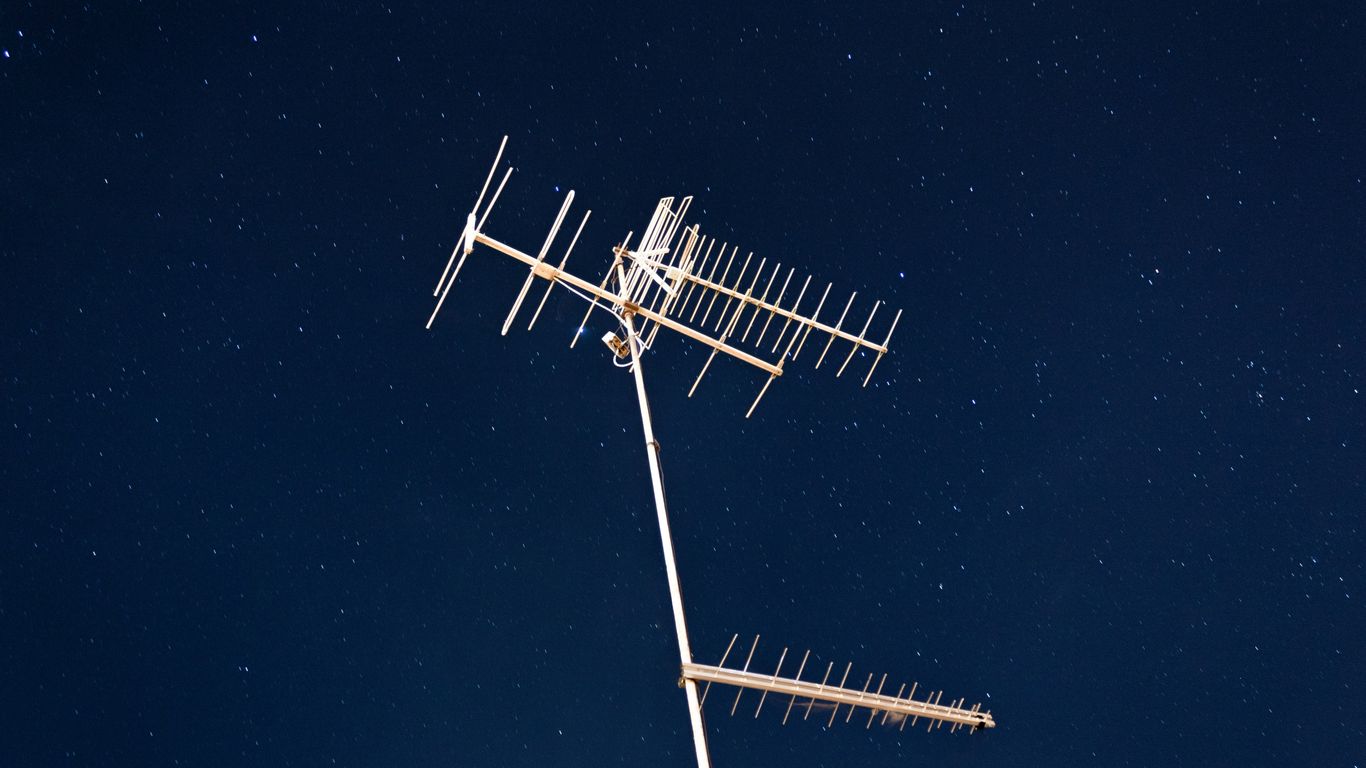

Drag Sails for Accelerated Decay

One of the most common passive methods involves drag sails. These are basically large, lightweight sheets that deploy from the satellite. Imagine a kite, but in space. When unfurled, these sails catch more of the sparse atmosphere that exists even in orbit. This increased surface area means more friction, which slows the satellite down. As it slows, its orbit gets lower, and eventually, it re-enters the atmosphere and burns up. It’s a pretty neat trick to speed up the natural decay process, especially for satellites in lower orbits where atmospheric drag is already a factor.

Deployable Booms and Tethers

Similar to drag sails, deployable booms and tethers are also used to increase a satellite’s size and thus its interaction with the atmosphere. Booms are rigid structures that extend outwards, while tethers are long, flexible cables. Some tethers can even be electrodynamic, meaning they can generate a small electrical current as they move through the Earth’s magnetic field, creating a force that helps pull the satellite down. These methods are all about making the satellite a bigger target for atmospheric drag, nudging it out of orbit more efficiently.

The Exo-Brake Concept

The Exo-Brake is another interesting passive idea. It’s essentially a deployable structure designed to significantly increase a satellite’s drag. Unlike a simple sail, it might have a more complex shape, like a parachute or a series of fins, to maximize its interaction with the thin upper atmosphere. The goal is to create a substantial braking effect without needing any active propulsion. It’s a bit like adding a big air brake to the satellite, forcing it to slow down and begin its descent.

Active Satellite Deorbiting Solutions

While passive methods are getting more attention, sometimes you just need a more direct approach to get rid of old satellites. That’s where active deorbiting solutions come in. These aren’t built into the satellite from the start; instead, they’re external systems or services designed specifically to grab onto a defunct spacecraft and bring it down.

Dedicated Deorbiting Service Vehicles

Think of these as specialized tow trucks for space. Companies are developing and even testing dedicated spacecraft whose sole purpose is to rendezvous with an old satellite. Once docked, they can either push the satellite into a lower orbit where it will naturally burn up faster, or guide it for a controlled reentry. This is becoming a big deal, especially with the massive satellite constellations planned for the coming years. It’s a way to actively manage the end-of-life for these complex systems.

Rendezvous and Removal Systems

This is a bit more hands-on. These systems are designed to actively approach and capture a piece of space junk or an entire satellite. It’s not just about nudging it; it’s about making a secure connection. Once attached, the removal system can then maneuver the target object to a safe disposal orbit. This is a more complex operation, requiring precise navigation and control, but it offers a robust solution for larger debris or satellites that might not have any deorbiting capability built-in.

Harpoons and Nets for Debris Capture

For when a simple docking isn’t feasible, or for capturing smaller, tumbling pieces of debris, more unconventional methods are being explored. Harpoons, for instance, could be fired to spear a satellite or large debris fragment, allowing a service vehicle to then pull it away. Nets are another idea, designed to entangle and capture debris. These methods are still in development but show promise for dealing with a wider range of space junk. While they might sound a bit dramatic, they represent innovative thinking for tackling the growing problem of orbital clutter.

Factors Influencing Orbital Decay

So, you’ve got a satellite up there, and you want it to come back down. Easy, right? Well, not exactly. A bunch of things actually affect how quickly a satellite decides to leave orbit. It’s not just about flipping a switch; nature and the satellite’s own design play a big role.

Ballistic Coefficient and Solar Weather

Think of the ballistic coefficient (BC) as a measure of how much a satellite resists changes in its motion. It’s basically a ratio of its mass to its surface area, with a bit of math thrown in for drag. A higher BC means it’s harder to push around, so it’ll stick around longer. A lower BC, on the other hand, means it’s more easily affected by the thin atmosphere way up there, helping it to fall back to Earth faster. This is why some satellites are designed with larger surface areas relative to their mass to speed up their demise.

Then there’s solar weather. When the sun is having a party, it sends out more energy, which heats up and expands Earth’s upper atmosphere. This makes the atmosphere denser at satellite altitudes. More density means more drag, and more drag means a quicker orbital decay. So, a satellite might fall faster during a solar maximum than during a solar minimum. It’s like trying to run through water – the denser the water, the harder it is to move.

Altitude and Natural Decay Rates

This one’s pretty straightforward. The higher a satellite is, the less atmospheric drag it experiences. Satellites in lower orbits, say below 400 km, will naturally decay and burn up in the atmosphere within a few years. But once you get above 500 km, things get a lot more stable. Some satellites launched at these higher altitudes might not decay for 25 years or even longer if nothing is done to help them along. It’s a big difference, and it’s why regulations often focus on ensuring satellites in higher orbits have a plan to get out.

The Role of Initial Orbit Insertion

Where you put a satellite when you first launch it matters a lot. It turns out there are these ‘natural deorbiting highways’ in Low Earth Orbit. By carefully choosing the initial orbit, especially the inclination (the angle relative to the equator), you can sometimes set a satellite on a path for a quicker natural decay. Certain inclinations, like around 41 degrees, can put a satellite in a sweet spot where various gravitational forces and solar radiation effects conspire to pull it down faster. It’s like giving it a gentle nudge in the right direction from the start. However, small satellites often don’t get to pick their exact orbit, and many end up in sun-synchronous orbits, which aren’t always near these natural decay corridors. So, while it’s a neat trick, it’s not always an option for everyone.

Regulatory Landscape and Compliance

Mandatory Deorbiting Rules

So, the big question is, who makes sure satellites don’t just become space junk? Well, there are rules, and they’re getting stricter. For a long time, it was kind of the Wild West up there, but now, countries and international bodies are putting their foot down. The general idea is that when a satellite’s done its job, it needs to be taken out of the way. This usually means either burning up in the atmosphere or being moved to a ‘graveyard’ orbit, which is basically a less crowded area.

Most regulations focus on getting satellites out of crowded orbits, especially Low Earth Orbit (LEO), within a certain timeframe after their mission ends. For LEO, this is often set at 25 years, though many operators are aiming for much shorter deorbit times, like under 5 years, to be safe. It’s all about preventing collisions and keeping orbits usable for future missions. The goal is to make sure space stays accessible and safe for everyone, not just for the next few years, but for generations to come.

Controlled Reentry Trajectories

When a satellite is deorbited, it’s not just a free-for-all. We’re talking about controlled descents. This means planning exactly where and when the satellite will re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. The aim is to have any surviving pieces land in unpopulated areas, like the South Pacific Ocean’s ‘spacecraft cemetery’. This requires precise calculations and often specific maneuvers to guide the satellite down. It’s a bit like planning a flight path, but with the added challenge of dealing with orbital mechanics and atmospheric drag. Getting this right is super important to avoid any unexpected splashdowns in populated zones.

International Deorbiting Standards

Making rules for space is tricky because space is, well, everywhere. So, different countries have their own takes, but there’s a push for global agreement. Organizations like the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) are working on guidelines. The idea is to get everyone on the same page about what’s acceptable and what’s not when it comes to managing space debris. This includes things like:

- Sharing data on satellite orbits and potential collision risks.

- Developing common best practices for satellite design to minimize debris.

- Establishing clear responsibilities for deorbiting.

It’s a slow process, but having international standards helps create a more predictable and sustainable space environment for everyone involved. Think of it as setting the ground rules for a global game, so everyone knows how to play fair.

Commercial Opportunities in Orbital Sustainability

So, space debris is a big problem, right? But it turns out, it’s also creating some interesting new business ideas. Think of it as turning a mess into a market. Companies are starting to see that cleaning up space, or at least making it less messy, can actually be profitable.

Active Debris Removal as a Service

This is probably the most direct way businesses are getting involved. Instead of just complaining about junk in orbit, some companies are building the tools to go get it. They’re developing things like robotic arms, nets, or even harpoons to grab old satellites and defunct rocket parts. Once captured, these items can be deorbited safely. It’s like a space towing service, but for orbital trash. The idea is that satellite operators, or even governments, will pay these companies to take away their old, unwanted hardware. It’s a service that’s becoming more necessary as orbits get more crowded.

In-Orbit Servicing for Longevity

Another angle is making satellites last longer. Why launch a new one when you can fix or refuel the old one? This is where in-orbit servicing comes in. Companies are working on technologies to dock with existing satellites, perform repairs, top up fuel tanks, or even upgrade components. By extending a satellite’s operational life, we reduce the need for new launches, which in turn means less new debris being created. It’s a proactive approach to sustainability. Think of it like getting an oil change and tune-up for your car instead of buying a new one every few years. This also opens up opportunities for specialized components and expertise.

Public-Private Partnerships for Deorbiting

Nobody can solve this space junk issue alone. That’s why we’re seeing more collaborations between government agencies and private companies. Agencies like NASA or the ESA might have the research and regulatory backing, while private companies bring the innovation and the drive to make a business out of it. These partnerships can help fund the development of new deorbiting technologies and services. They can also help set standards and create a framework for how these new businesses operate. It’s a way to share the costs and the risks, and hopefully speed up the development of solutions that keep space usable for everyone.

Future of Satellite Deorbiting

So, what’s next for getting rid of old satellites? It’s a pretty big deal, and things are definitely moving forward. We’re seeing a lot more focus on making sure satellites don’t just become space junk when their job is done.

Advancements in Deorbiting Hardware

We’re not just talking about theoretical ideas anymore. Companies and space agencies are actually building and testing new gadgets to help satellites come back down. Think about drag sails, which are getting better and more reliable, or even more complex systems that can grab onto defunct satellites. The goal is to make these devices smaller, lighter, and more effective. Some are designed to be built right into the satellite from the start, while others are separate services that can be called upon when needed. It’s all about having more options to deal with satellites at the end of their life.

The Importance of Space Traffic Management

As more satellites go up, managing them becomes a huge challenge. Imagine a busy highway, but in space. We need systems that can track everything, predict where things are going, and help prevent collisions. This isn’t just about deorbiting; it’s about making sure the whole space environment stays usable. Good space traffic management means we can better plan when and how satellites should deorbit, reducing risks and making sure we don’t clutter up important orbital paths. It’s like having air traffic control, but for space.

Innovations in Deorbiting Strategies

Beyond just hardware, the way we think about deorbiting is changing. We’re looking at more creative ways to get satellites down safely. This includes things like using natural orbital mechanics to our advantage, or developing services that can refuel or reposition satellites to extend their useful life, delaying the need for deorbiting. The big push is towards making space more sustainable, so future generations can still use it. It’s a mix of new tech, better planning, and a general shift towards responsible space use.

Looking Ahead: Keeping Space Clean

So, we’ve talked about why getting rid of old satellites is a big deal and looked at some of the ways folks are trying to do it. It’s not just about cleaning up; it’s about making sure we can keep using space for all the cool things it does for us, from weather forecasts to internet. There are a bunch of smart people and companies working on this, developing new gadgets and services to bring these retired satellites back down safely. It’s a complex problem, for sure, but seeing the progress being made gives you hope that we can manage this space junk situation and keep the skies clear for future missions and discoveries. It’s definitely something to keep an eye on as more satellites go up.