It’s pretty wild to think about how far we’ve come with making things. For ages, if you wanted to build something, you had to shape it from a bigger piece or put smaller pieces together. Then, around the 1980s, a whole new way of thinking started to take hold. Instead of taking away material, people figured out how to build things up, layer by layer. This article is going to look at how that whole idea got started and what the very first technology used in additive manufacturing was.

Key Takeaways

- The earliest ideas for building objects layer by layer date back to the early 1980s, with Dr. Hideo Kodama exploring photopolymerization for rapid prototyping.

- Stereolithography (SLA), developed by Charles Hull in 1984, is widely recognized as the first actual additive manufacturing process, using lasers to cure liquid resins.

- Hull’s invention not only laid the groundwork for SLA but also led to the founding of 3D Systems, marking the commercial beginning of this technology.

- Following SLA, other foundational additive manufacturing techniques like Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) and Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) emerged in the late 1980s.

- These early methods, though primitive by today’s standards, were the crucial first steps that paved the way for the diverse and advanced additive manufacturing technologies we use now.

The Genesis of Additive Manufacturing

Before we got to the fancy machines we see today, the idea of building things layer by layer was brewing for a while. It all really started to take shape in the early 1980s. Think of it as the very first sparks of an idea, long before it became a full-blown industry.

Dr. Hideo Kodama’s Early Prototyping

Back in 1981, a researcher named Dr. Hideo Kodama in Japan was working on something pretty neat. He was trying to figure out how to make prototypes faster. His idea involved using a special liquid material that hardened when exposed to light. He even filed a patent for this concept, which was basically an early form of 3D printing. He envisioned using light to solidify layers of material to build up a 3D object. Unfortunately, he ran into some funding issues, and his project never quite got off the ground. It’s a shame, really, because he was definitely onto something big.

The Concept of Layering and Photopolymerization

Kodama’s work touched on two key ideas that are still super important in additive manufacturing today: layering and photopolymerization. Layering is just what it sounds like – building an object one thin slice at a time. Photopolymerization is the fancy term for using light, usually UV light, to harden or cure a liquid material. This combination is what allows these machines to create complex shapes from the ground up. It’s like building with digital LEGOs, but instead of snapping bricks together, you’re solidifying liquid.

Challenges and Unfulfilled Potential

Even though Dr. Kodama had a great idea, there were a lot of hurdles. Getting the materials just right, controlling the light source precisely, and the sheer cost of developing such new technology were all major challenges. Without the right backing and further development, his initial concept remained largely theoretical. It showed the potential, but the practical execution was still a long way off. It’s a classic case of having a brilliant idea ahead of its time, waiting for the right moment and the right resources to make it a reality.

Pioneering the First Additive Manufacturing Process

So, we’ve touched on the early ideas, but who actually got the ball rolling with the first real additive manufacturing process? That honor goes to Charles Hull. Back in 1986, he patented a method called stereolithography, or SLA for short. This was a pretty big deal because it was the first time someone had figured out how to build a 3D object layer by layer using light.

Charles Hull and Stereolithography

Charles Hull, who later co-founded 3D Systems, basically invented SLA. His idea was to use a special liquid called a photopolymer. When this liquid is hit by a specific type of light, usually from a UV laser, it hardens. Hull’s system would trace a pattern onto the surface of this liquid, hardening it to form a thin layer of the object. Then, the platform would move down a tiny bit, and another layer would be traced and hardened on top of the previous one. This process of building objects one thin slice at a time was revolutionary. It was a completely new way to make things, moving away from traditional subtractive methods where you cut material away from a larger block.

The Laser Curing of Photopolymer Resins

The magic behind SLA is the photopolymer resin. Think of it like a liquid plastic that reacts to UV light. The laser in the SLA machine is super precise. It scans across the surface of the resin, following the design of the object for that specific layer. Where the laser hits, the resin solidifies. Once a layer is done, the platform dips, and the laser starts on the next layer. It’s a bit like drawing with light in a vat of goo, but the result is a solid object.

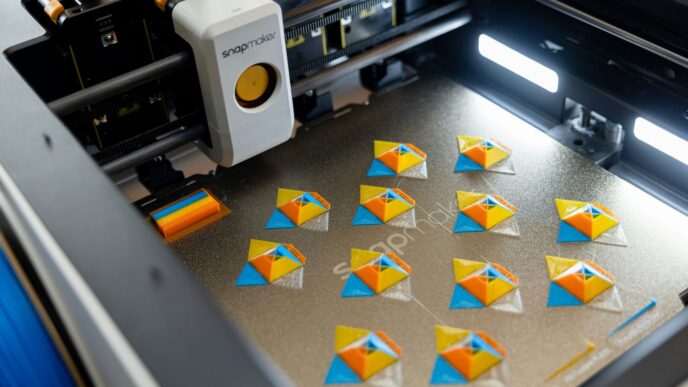

Here’s a simplified look at how it works:

- A vat is filled with liquid photopolymer.

- A UV laser beam precisely traces the shape of the object’s first layer onto the resin.

- The exposed resin hardens, forming the first layer.

- The platform lowers slightly, and the process repeats for the next layer.

- This continues until the entire object is built from the bottom up.

Commercialization and the Birth of 3D Systems

Hull didn’t just invent the technology; he saw its potential for business. In the same year he patented SLA, 1986, he co-founded 3D Systems. This company was created specifically to bring stereolithography to the market. It was the first company dedicated to this new form of manufacturing, and it really kicked off the commercial side of what we now call 3D printing. Suddenly, businesses could start using this technology for rapid prototyping, which meant they could create physical models of their designs much faster and cheaper than before. It was the dawn of a new era in making things.

The Dawn of Rapid Prototyping Technologies

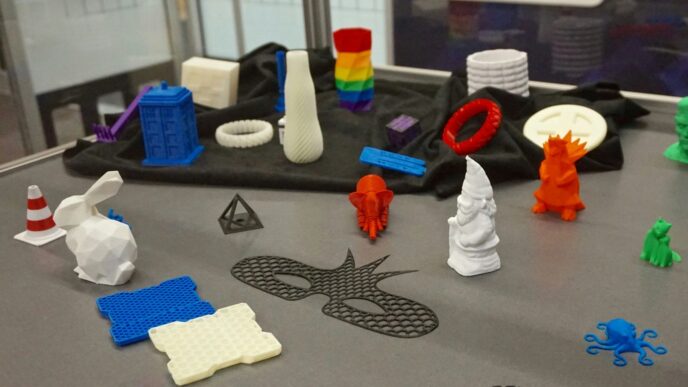

So, after the initial ideas and patents started popping up, things really began to pick up speed in the late 80s and early 90s. This was when the concept of "rapid prototyping" started to take hold, meaning companies could actually make a physical model of their designs pretty quickly, instead of waiting weeks or months.

Selective Laser Sintering Emerges

This whole idea of using a laser to build things layer by layer got a lot of attention. Selective Laser Sintering, or SLS, was one of those big steps. Basically, it uses a laser to fuse together tiny particles of powder – think plastics, metals, or even ceramics. It’s like drawing with a laser, but instead of ink, you’re melting powder into a solid shape. Carl Deckard was a big name here, working on this technology back in the late 80s. It took a while for it to become something you could actually buy, though; commercial SLS printers didn’t really show up until the mid-2000s.

Fused Deposition Modeling Takes Shape

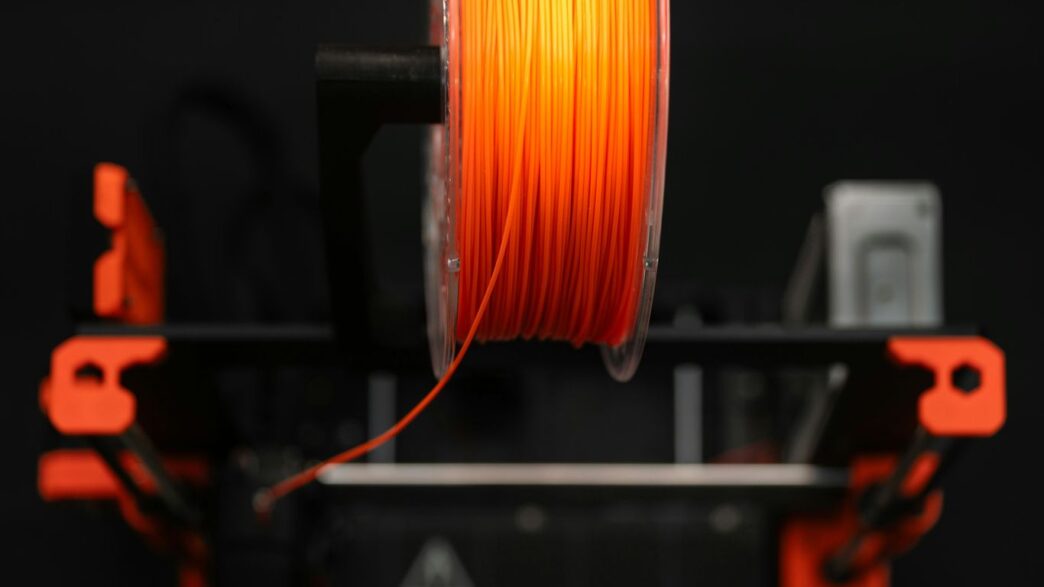

Then there’s Fused Deposition Modeling, or FDM. You might know it better by its other name, Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). This is probably the most common type of 3D printing you see today, especially for home users. Scott Crump invented it in 1989 and went on to found Stratasys, a company that’s still a major player. FDM works by melting a plastic filament and then extruding it, layer by layer, onto a build platform. It’s kind of like a very precise, computer-controlled hot glue gun. The RepRap project, which started in 2005, really pushed this technology forward by making it open-source and encouraging people to build their own printers. This led to a bunch of companies, like MakerBot, popping up in the late 2000s, selling kits and making 3D printing more accessible.

Innovations in the 1990s

The 90s were a busy time for additive manufacturing. Besides SLS and FDM getting their start, other methods were being explored. For instance, Solid Ground Curing (SGC) used UV light to harden liquid photopolymers, and Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM) involved gluing and cutting layers of material like paper or plastic. While these might not be as common now, they were part of the experimental phase that paved the way for what we have today. It was all about figuring out different ways to build objects from the ground up, one slice at a time.

Evolution Beyond Prototyping

Early Applications in Manufacturing

While 3D printing started out as a way to quickly make prototypes, it didn’t take long for people to realize it could do much more. Companies began looking at how these machines could actually be used to make real parts, not just models. This shift was huge. Instead of just checking a design, manufacturers could now produce functional components, tools, and even end-use products directly. This meant less reliance on traditional manufacturing methods for certain items, speeding up production lines and allowing for more complex designs that were previously impossible or too expensive to make.

Advancements in Material Science

The real game-changer, though, was the development of new materials. At first, the options were pretty limited, mostly plastics that were good for models but not much else. But as the technology matured, so did the materials. We started seeing plastics that could handle high temperatures, resist chemicals, and even had conductive properties. Then came the big leap: metal printing. Being able to print with steel, aluminum, and titanium opened up a whole new world of possibilities for industries like aerospace and automotive. It wasn’t just about making plastic trinkets anymore; it was about creating strong, durable parts that could withstand serious stress. The introduction of "bio-inks" for printing tissue is another example of how far materials have come, hinting at future medical applications.

The First Metal 3D Printer

Speaking of metal, the development of the first metal 3D printers was a massive step. Before this, if you needed a metal part, you were pretty much stuck with subtractive manufacturing – cutting away material from a block of metal. This was often wasteful and time-consuming. Additive manufacturing with metals changed that. Technologies like Selective Laser Melting (SLM) and Electron Beam Melting (EBM) allowed for the creation of intricate metal parts layer by layer, directly from a digital file. This meant:

- Reduced material waste: Only the material needed is used.

- Complex geometries: Designs previously impossible to machine could now be printed.

- On-demand production: Parts could be made as needed, reducing inventory.

This innovation really started to blur the lines between prototyping and actual production, showing that 3D printing technology was invented in 1984 by Charles Hull, who patented stereolithography, the first method for creating 3D objects from digital designs. This marked the beginning of a technological revolution. was capable of much more than just making quick models.

Transformative Impact Across Industries

Revolutionizing Healthcare and Medicine

Additive manufacturing has really changed the game in healthcare. Think about it – instead of waiting for standard-issue implants, doctors can now create custom-fit ones. This means hip replacements or dental crowns can be made specifically for a patient’s anatomy. It’s not just about implants, either. Researchers are working on printing tissues and even organs, which could eventually help with transplant shortages. It’s pretty wild to imagine.

Enhancements in Aerospace Engineering

The aerospace industry was one of the first to really see the benefits. You know how every ounce counts when you’re building a plane or a rocket? Well, 3D printing allows engineers to design parts that are lighter but just as strong, if not stronger, than traditionally made ones. This can lead to better fuel efficiency and improved performance. Plus, they can print complex internal structures that would be impossible to make any other way. They’ve even printed tools in space!

Automotive Industry Adoption

Cars are getting a lot of love from additive manufacturing too. While we’re not quite at the point of printing entire vehicles, car makers are using it a lot for creating prototypes. This speeds up the design process significantly. They can test out new ideas much faster and cheaper. Beyond prototypes, they’re also using it for making specialized tools and even some end-use parts for low-volume production runs. It’s making manufacturing more flexible.

The First Technology Used in Additive Manufacturing Is Explored

Understanding Early Layering Techniques

When we talk about the very first steps in additive manufacturing, it’s easy to get lost in the modern marvels of 3D printing. But going back, the core idea was about building things up, layer by tiny layer. Think of it like stacking thin slices of material to form a complete object. This concept, while simple now, was revolutionary back then. It was a departure from traditional methods that often involved carving away material. The early pioneers were figuring out how to make something appear from nothing, or at least from a pool of raw material. It was a slow process, for sure, but it laid the groundwork for everything we see today. The initial attempts were focused on creating prototypes, quick models to test ideas before committing to expensive tooling. It was all about speed and iteration, a stark contrast to the lengthy manufacturing cycles of the past. This foundational concept of additive layering is what makes additive manufacturing possible.

The Role of Photopolymers in Initial Processes

So, how did these early machines actually build things? A big part of the answer lies in something called photopolymers. These are special liquids that have a neat trick: they harden when exposed to a specific type of light, usually ultraviolet (UV). Imagine a vat of this liquid. A light source, often a laser, would trace a pattern on the surface, hardening just that specific layer. Then, the platform would move down slightly, and another layer of liquid would be applied, and the laser would trace the next cross-section. This repeated process, layer by layer, is how the object took shape. It was a bit like drawing with light in a liquid. This method was key to the first successful additive manufacturing processes, allowing for intricate shapes that were previously impossible to create. The precision of the laser and the properties of the photopolymer were critical factors in the success of these early systems.

Comparing Early Additive Methods

While stereolithography (SLA) is often cited as the first true additive manufacturing process, it’s worth remembering that other ideas were brewing around the same time. Dr. Hideo Kodama, for instance, was exploring similar layering concepts using photopolymers back in 1981, though his work didn’t quite reach commercialization due to funding issues. Charles Hull’s SLA, patented in 1986, really brought the idea to life by using a UV laser to cure liquid photopolymer resins. This was a significant step. Around the same time, other researchers were looking at different ways to achieve the same goal. For example, Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), which uses a laser to fuse powdered materials, and Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), which extrudes melted plastic, were also being developed shortly after. Each method had its own set of materials and challenges, but they all shared that fundamental principle of building objects layer by layer. It was a period of intense innovation, with several different paths being explored simultaneously to achieve this new way of making things.

Wrapping It Up

So, looking back, it’s pretty wild to see how far additive manufacturing has come. From those early ideas in the 80s, like Dr. Kodama’s work and Chuck Hull’s stereolithography, it was all about making prototypes faster. Now, it’s everywhere, changing how we make everything from airplane parts to medical devices. It really started small, with just a few people tinkering, but it’s grown into something huge that’s still changing. It’s exciting to think about what’s next, but for now, it’s cool to know where it all began.