So, you want to know about metallization in semiconductor chips? It’s basically how we create the tiny metal pathways that let all the electronic bits talk to each other. Think of it like building roads on a microscopic level. Without these metal connections, your phone, computer, or any gadget wouldn’t work. We’ll chat about what it is, how it’s done, and some of the materials involved in making these essential semiconductor circuits.

Key Takeaways

- Metallization is the process of adding metal layers to semiconductor materials to create conductive pathways, which are vital for the functioning of electronic devices.

- Historically, aluminum was the go-to material for semiconductor metallization due to its good conductivity, adhesion, and ease of processing, though it has limitations like electromigration.

- Copper and gold have become more common in advanced semiconductor designs because they offer better conductivity and resistance to electromigration than aluminum, despite their own processing challenges.

- Various techniques are used to apply and pattern these metal layers, including physical vapor deposition (PVD), sputtering, and lithography, each with its own advantages for different applications.

- As chips get smaller and more complex, multilayer metallization schemes and advanced materials are developed to pack more components and improve performance, while also facing challenges like increased cost and manufacturing complexity.

Understanding Metallization In Semiconductor Circuits

So, what exactly is metallization in the world of semiconductors? Think of it as the wiring system for tiny electronic brains. It’s the process that connects all the different parts of a semiconductor device, allowing electricity to flow where it needs to go. Without it, your phone, computer, or any other gadget wouldn’t be able to do much at all.

The Role of Metallization in Semiconductor Devices

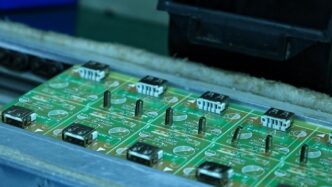

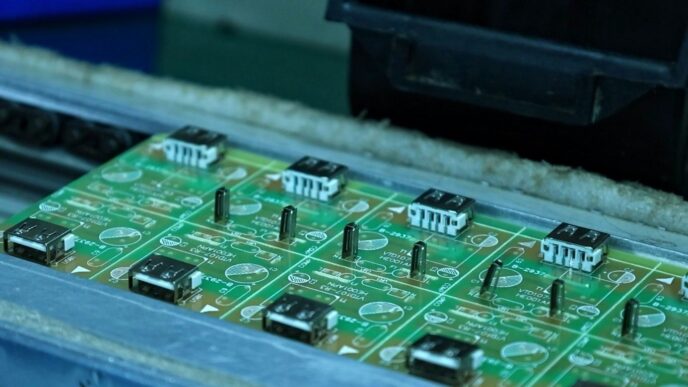

At its core, metallization is about creating conductive pathways on and between semiconductor components. These pathways are typically made of thin layers of metal. These metal lines are absolutely vital for transmitting signals and power throughout the chip. They act like the roads and highways for electrons, guiding them to their destinations. The complexity of these pathways has grown immensely over the years, especially with the development of three-dimensional integrated circuits, where layers are stacked on top of each other.

Connecting Semiconductor Substrates with Metal Lines

The actual process of connecting a semiconductor substrate with these metal lines is what we call "metallization." It’s not just about laying down metal; it’s about creating a reliable electrical connection. The metal itself plays a role in holding its own ions together through electrostatic attraction, which is stronger than any disruptive forces. This stability is key for the long-term performance of the device.

The Importance of Metal Lines in Holding Ions

When we talk about metal lines holding ions, it refers to the internal structure of the metal itself. The atoms within the metal are ionized, and they are held in place by strong electrostatic forces. This internal cohesion is what allows the metal line to maintain its integrity and conductivity under various operating conditions. It’s a bit like how bricks hold together to form a wall; the metal ions form a stable structure that can carry electrical current without falling apart.

Key Metallization Processes and Materials

When we talk about making semiconductor circuits work, the materials and how we put them down are super important. It’s not just about picking any metal; the process has to be just right for the job.

The Manganese–Molybdenum Process for Ceramics

For certain materials, like ceramics, a common method is the manganese-molybdenum process. It starts with a sort of paint made from molybdenum, manganese oxide, some glass bits, and a liquid to carry it all. This mixture gets fired at a really high temperature, around 1500°C, in an atmosphere that doesn’t have much oxygen, like hydrogen. During this firing, the glass in the paint actually bonds with the ceramic, and the metal particles stick together. After that, the surface is usually plated with nickel, either through an electroless or electroplating method. Then, it might get another firing or go straight to being joined with another piece using a brazing metal. A common brazing metal is a mix of silver and copper, which melts at a relatively low temperature of 780°C. This process works well because the ceramic needs to have a glassy part for it to stick properly. If that’s not possible, other ways like vapor deposition or ion sputtering are used instead.

Alternative Metallization Techniques: Vapor Deposition and Sputtering

When the manganese-molybdenum process isn’t the best fit, or if you need a different kind of surface, techniques like vapor deposition and sputtering come into play. These methods are good for applying metal coatings directly onto surfaces. They can create high-quality, uniform layers with fine control over thickness. Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD), for instance, is known for its environmental friendliness and ability to produce excellent coatings, though it can be slower. Vapor Phase Deposition, on the other hand, can be faster and cover larger areas, but it often requires more expensive equipment and specific environmental conditions. These techniques are useful when you can’t rely on the ceramic having that specific glassy phase needed for other methods. They offer a way to get a reliable metal layer down, which is key for creating defined patterns in electronics.

Precious Metals in High-Temperature Applications

Sometimes, the job requires metals that can handle a lot of heat, especially when joining components that are sensitive to high temperatures. In these cases, precious metals like silver, or combinations such as silver/palladium and silver/platinum, are often used. Gold is another option. These metals are chosen because they maintain their integrity and conductivity even when things get really hot. The process of applying these metals can be quite involved, requiring careful control over temperature and atmosphere. It’s not a simple task, and getting it right consistently takes a good amount of technical skill and experience. This is particularly relevant in fields like energy engineering where components might operate under extreme thermal conditions.

Advanced Metallization Schemes for Integrated Circuits

As chips get smaller and pack more transistors, the way we connect everything on them has to get smarter. We can’t just keep laying wires flat on the surface forever; there’s simply not enough room. This is where advanced metallization schemes come into play, allowing us to build upwards and create more complex circuits.

Multilayer Metallization for Increased Chip Density

Think of it like building a city. Instead of spreading everything out on one level, we start building skyscrapers. Multilayer metallization does just that for chips. By stacking multiple layers of metal interconnects, separated by insulating materials, we can significantly increase the number of components on a single chip without making the chip itself much larger. This approach was predicted to involve 15 to 20 metal layers years ago, and it’s how we achieve the dense circuitry we see today. It’s a clever way to overcome the limitations of surface area.

The Dual-Metal Stack: Barrier Layers and Interconnects

A common setup involves a dual-metal stack. It usually starts with a barrier layer, often formed by treating the silicon surface. This layer does a couple of important things: it lowers the electrical resistance between the silicon and the metal, and it can stop certain metals, like pure aluminum, from reacting undesirably with the silicon. Then comes the insulating layer, called the inter-metal dielectric (IMD). This layer is key for keeping the different metal layers from shorting out. After that, we etch tiny holes, called vias or plugs, down to the first metal layer. These holes are then filled with conductive material, creating connections between layers. Finally, the second metal layer is deposited and patterned. This whole process of depositing insulators, creating vias, and adding metal is repeated for each subsequent layer.

Challenges and Considerations in Multilayer Systems

While multilayer metallization is powerful, it’s not without its headaches. Building these intricate stacks is more expensive, and getting a high yield can be tricky. A big part of the challenge is keeping the wafer surface and all the intermediate layers perfectly flat. If things aren’t planar, it makes it much harder to create good, reliable current-carrying paths. Plus, dealing with different materials and ensuring they all play nicely together requires careful process control. The backside metallization process, for instance, is a critical step in fabricating many advanced semiconductor devices, and managing multiple layers adds complexity.

Here’s a quick look at some common materials used in these stacks:

| Layer Type | Common Materials | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier Layer | Titanium Nitride (TiN), Tantalum Nitride (TaN) | Prevents diffusion, improves adhesion, reduces contact resistance |

| Interconnect | Copper (Cu), Aluminum (Al) | Conducts electrical signals between components |

| Inter-Metal Dielectric (IMD) | Silicon Dioxide (SiO2), Low-k Dielectrics | Insulates metal layers from each other |

| Via/Plug | Tungsten (W), Copper (Cu) | Connects different metal layers vertically |

Getting these layers right is a constant balancing act between performance, cost, and reliability.

Common Metallization Materials in Semiconductor Fabrication

When we talk about making semiconductor chips, the metal bits are super important. They’re like the highways for all the electrical signals zipping around. For a long time, aluminum was the go-to material for this. It’s pretty cheap and easy to work with, which made it a solid choice for early chips. You’d often see it used in its pure form or mixed with a bit of silicon to make it more stable.

Aluminum: The Historical Standard

Aluminum’s reign as the king of chip wiring lasted for decades. Its low cost and good conductivity made it a natural fit for the intricate pathways needed in integrated circuits. However, pure aluminum had its issues. It could sometimes react with the silicon in the chip itself, creating brittle compounds that weren’t great for long-term reliability. Plus, it wasn’t the strongest material when it came to handling high currents without breaking down.

Aluminum-Silicon Alloys and Eutectic Formation

To tackle some of aluminum’s weaknesses, engineers started using aluminum-silicon alloys. Adding a small amount of silicon, usually around 1%, helped prevent a problem called "spiking." This is where the aluminum could actually penetrate into the silicon substrate, causing short circuits. The addition of silicon also helped manage the melting point. When the alloy reaches a specific ratio of aluminum to silicon (the eutectic point), it melts at a lower temperature. This can be useful in certain manufacturing steps, but it also means you have to be careful not to accidentally melt your connections during other high-temperature processes.

The Transition to Copper and Gold

As chips got more complex and signals needed to travel faster, aluminum started showing its limits. Its electrical resistance is higher than some other metals, meaning signals slow down and generate more heat. This led to a big shift towards other materials. Copper became the new standard for many advanced chips because it conducts electricity much better than aluminum and is more resistant to electromigration, a phenomenon where metal atoms move under high current densities, eventually causing failures. Gold is also used, especially in high-performance applications or where extreme reliability is needed, though its cost is a significant factor. The move to these new materials, like copper, required developing entirely new manufacturing front-end metallization techniques and processes to handle them effectively.

Deposition Techniques for Metallization Layers

So, how do we actually get these metal layers onto the semiconductor wafers? It’s not like we’re just painting them on. There are several ways to do this, and each has its own pros and cons. The method chosen really depends on what kind of metal we’re using, the specific chip design, and how much we want to spend.

Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) and Its Advantages

Physical Vapor Deposition, or PVD, is a pretty common method. Think of it as a way to "evaporate" a solid material and then have it condense onto the wafer surface. It’s great for creating really thin, uniform layers. You get a lot of control over the thickness and the quality of the coating. It’s also pretty good for the environment, which is a plus. The downside? It can be a bit slow and the equipment isn’t exactly cheap.

Vapor Phase Deposition for High-Quality Coatings

Similar to PVD, Vapor Phase Deposition (VPD) also involves turning a material into a vapor. However, it often involves chemical reactions in the vapor phase to deposit the film. This can lead to some really high-quality coatings, and it’s often faster than PVD, especially for larger areas. But, you’re looking at some serious equipment costs, and the process can be sensitive to environmental conditions. You also need to make sure the surface is prepped just right.

Electroless Plating and Electroplating Methods

Then there’s plating. Electroless plating uses a chemical reaction to deposit metal without any electricity. It’s nice because it coats surfaces really evenly, even in tricky spots, and the metal sticks well. The trade-off is that it’s usually a slower process and can be more expensive. Electroplating, on the other hand, uses electricity to deposit the metal. It’s generally faster, sticks well, and is less costly. However, you need a conductive surface to start with, and sometimes the process can make the metal brittle. Plus, the type of plating solution you use really matters.

Here’s a quick look at how some of these stack up:

| Process | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Vapor Deposition | High-quality, uniform coating, fine control | Expensive, slow deposition rate |

| Vapor Phase Deposition | High quality, fast deposition, large area | High equipment cost, strict environmental needs |

| Electroless Plating | Uniform coating, good adhesion, wide use | Slow rate, high cost, environmental concerns |

| Electroplating | Fast deposition, good adhesion, low cost | Requires conductive surface, potential brittleness |

Patterning and Precision in Metallization

So, you’ve got your semiconductor substrate, and you’ve figured out what metal you want to use. Great! But how do you get that metal exactly where it needs to be, in the intricate patterns that make up a chip? That’s where patterning and precision come in. It’s all about creating defined patterns, which is pretty much the main event for building functional devices, especially the electronic kind.

Lithography for High-Accuracy Metal Patterning

When we talk about super-fine details, lithography is often the go-to method. Think of it like using a stencil, but on a microscopic scale. Light is used to transfer a pattern from a mask onto a light-sensitive material (photoresist) on the metal layer. Then, the unwanted metal is etched away. This process is known for its high accuracy and scalability, making it a workhorse in the industry. However, it’s not exactly cheap or simple, and it can get complicated when you’re trying to pattern really large areas. Getting that precise overlay alignment for successive lithography layers is a big deal, and current methods still have their challenges.

Screen Printing for Wider Applicability

Now, if you need something a bit more forgiving or cost-effective, screen printing might be the answer. It’s a bit like printing on a t-shirt, but with conductive inks. You push ink through a mesh screen with a pattern on it, directly onto the substrate. This method is pretty versatile and can be done at a lower cost, especially for larger production runs. The downside? You’re not going to get the same level of detail as lithography. The patterns are usually less precise, and you can’t create super complex designs. It’s great for simpler circuits or applications where extreme precision isn’t the top priority.

Direct Writing and Electrohydrodynamic Printing

For even more flexibility, especially in research or for custom designs, direct writing techniques come into play. These methods allow you to draw the metal pattern directly onto the surface without needing a mask. Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing is one such technique. It uses electric fields to precisely control the flow of a liquid metal ink. This offers high resolution and the ability to print with various metals, and it’s relatively low cost to get started. The trade-off is that it can be slow, and the success really depends on the specific metal ink you’re using and how skilled the operator is. It’s a cool way to experiment with new designs or create prototypes quickly.

Challenges and Future Directions in Metallization

So, we’ve talked a lot about how metallization works and the materials we use. But it’s not all smooth sailing, right? There are some real headaches in this field, and folks are constantly trying to figure out better ways to do things.

One big issue is something called electromigration. Basically, when current flows through these tiny metal lines, especially at higher temperatures, the metal atoms can start to move around. It’s like they get pushed along by the electrons. Over time, this can cause voids to form in one spot and build-ups in another, which can eventually break the connection or cause shorts. Preventing electromigration is a huge deal for making chips last longer and work reliably. Researchers are looking at different metal alloys and even adding barrier layers to keep those atoms in place. It’s a constant battle to keep the metal lines stable.

Then there’s the whole world of 3D printing and how it fits into metallization. While 3D printing offers amazing design freedom, getting really precise metal patterns onto complex 3D shapes is still tricky. We’re seeing improvements, but making it work for high-density circuits, like those found in the back end of line (BEOL) of advanced chips, is a tough nut to crack. The goal is to get better at printing these intricate metal structures without defects. This is key for scaling the back end of line in advanced semiconductor logic devices.

Another area getting a lot of attention is selective metallization. This means being able to put metal exactly where you want it, and nowhere else. It’s especially interesting for new materials like functional polymers. Imagine printing electronic circuits directly onto flexible plastics. Right now, achieving this kind of precision, especially on complex, non-flat surfaces, is a challenge. We need methods that are both accurate and scalable. Some promising techniques include photochemical methods, though achieving selectivity is still a hurdle.

Here’s a quick look at some of the ongoing challenges:

- Electromigration: Metal atom movement under current stress.

- 3D Printing Precision: Achieving fine metal features on complex 3D structures.

- Selective Deposition: Depositing metal only on desired areas.

- Material Compatibility: Ensuring metals work well with new substrate materials.

It’s a busy field, with a lot of smart people working on these problems. The future likely holds new materials, smarter deposition techniques, and maybe even some clever ways to combine different processes to overcome these hurdles and keep making our electronics smaller, faster, and more capable.

Wrapping It Up

So, we’ve talked a lot about metallization, which is basically how we get those tiny metal lines onto semiconductor chips. It’s not just about slapping some metal on there; there are different ways to do it, like using paints that get fired at super high temps or plating with nickel. And then there’s the whole multilayer thing, where you stack up layers of metal and insulation to fit more stuff onto a chip. It sounds complicated, and honestly, it is. But it’s this intricate process that makes all our electronics work. Without these metal pathways, your phone, your computer, everything, just wouldn’t do a thing. It’s pretty wild when you think about it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is metallization in computer chips?

Metallization is like drawing tiny metal roads on a computer chip. These metal roads, called lines, connect all the different parts of the chip so they can talk to each other and work together. Without these metal roads, the chip wouldn’t be able to do anything!

Why are metal lines so important in chips?

Think of metal lines as the highways for electricity. They carry signals and power all over the chip. They’re crucial because they hold tiny charged particles, called ions, together. This strong connection allows electricity to flow reliably, which is essential for the chip to function correctly.

What are the most common metals used for these tiny roads?

In the past, aluminum was the go-to metal for these connections because it was easy to work with and didn’t cause problems with silicon. However, newer chips often use copper or gold. Copper is a better conductor than aluminum, meaning electricity flows through it more easily, and gold is used in special cases because it’s very resistant to corrosion.

How do they create these super-thin metal lines?

Making these tiny metal lines involves a few steps. One common way is called ‘Physical Vapor Deposition’ (PVD), where metal is turned into a gas and then coats the chip surface. Another method is ‘vapor phase deposition,’ which is similar but can create very high-quality coatings. Sometimes, they also use plating techniques, like electroplating, which is similar to how jewelry is plated.

What happens if the metal lines get too hot or too much electricity flows through them?

Sometimes, if a lot of electricity flows through a metal line, especially at higher temperatures, the metal ions can start to move around. This is called ‘electromigration.’ It can eventually break the metal line or cause a short circuit. Engineers have to design the metal lines carefully and sometimes use special materials to prevent this from happening.

Are there newer ways to make these metal connections?

Yes! Scientists are always finding new ways. One exciting area is ‘3D printing’ for metallization, which could allow for more complex connections in three dimensions, making chips even more powerful. They are also exploring ways to selectively add metal only where it’s needed, which can save resources and improve performance.